I wanted to write a piece on Nervous Norvus as the guy was pretty f.....d up in many ways, but mainly because it's the origin of 'ZORCH' (I think ?) as well as a lot of the hepcat lingo, 'Nervous Baby' and such like. Not only that, the mini album released by Big Beat all those moons ago, kind of left me a little scarred mentally....Anyway, I found this piece originally written by Phil Milstein for American Song & Poem Archive (Yeah,really !) and didn't think I could improve on it....appears that the website is dead now anyway so I've reproduced here....It's an American, formal perspective and doesn't really get the angle I'd be coming from but all the details are there !

I'm a twin-pipe papa and I'm feelin' fine

Hey man, dig that -- was that a red stop sign? [squeeeeeeeal ... kee-RASH!]

Transfusion, transfusion

I'm just a solid mess of contusions

Never never never gonna speed again.

Slip the blood to me, Bud.

|

| A Touch of Rockabilly Psychosis ! |

Drake maintained

split musical identities, his Singing Jimmy Drake discs being quickly-made and

generally uninspired affairs, while his Nervous Norvus recordings enjoyed the

greater bulk of his attention and imagination. As a result, the latter still

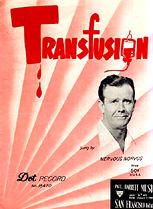

sound great today. Drake's six Nervous Norvus sides on Dot, released in a meteoric

burst during the middle of 1956, form the cornerstones of his legitimate career.

Add in some excellent unreleased demos and a small handful of other Nervous

Norvus records, and you have one of the richest bodies of novelty work ever

made, as inventive, as timelessly fresh and as purely musical as any since Spike

Jones. His songs zip and bounce along in jittery rhythms perfectly suited to

the "nervous" quality of his delivery; the lyrics cleverly written in accord

with conventional craft, yet informed by a unique middle-aged hepcat persona;

his cutting-edge sound effects (most of them created by his mentor, radio host

Red Blanchard) integrally woven so that music and effects are inseparable.

Drake maintained

split musical identities, his Singing Jimmy Drake discs being quickly-made and

generally uninspired affairs, while his Nervous Norvus recordings enjoyed the

greater bulk of his attention and imagination. As a result, the latter still

sound great today. Drake's six Nervous Norvus sides on Dot, released in a meteoric

burst during the middle of 1956, form the cornerstones of his legitimate career.

Add in some excellent unreleased demos and a small handful of other Nervous

Norvus records, and you have one of the richest bodies of novelty work ever

made, as inventive, as timelessly fresh and as purely musical as any since Spike

Jones. His songs zip and bounce along in jittery rhythms perfectly suited to

the "nervous" quality of his delivery; the lyrics cleverly written in accord

with conventional craft, yet informed by a unique middle-aged hepcat persona;

his cutting-edge sound effects (most of them created by his mentor, radio host

Red Blanchard) integrally woven so that music and effects are inseparable.  |

| Released in 2014. |

The early life of James William Drake was a knockabout one. He was born in 1912 in Memphis, and lived for a few years in Ripley, Tennessee, near the Arkansas border. (Other legendary recording artists who spent their early years in Ripley include Peetie Wheatstraw, aka The Devil's Son-In-Law, The High Sheriff Of Hell, and Tina Turner.) A chronic asthma condition led Drake's family to move him to California when he was seven, first to the Bay Area, then soon afterwards settling in Los Angeles. Like everyone else, the Drakes suffered hard through the Depression. In an article published in the Oakland Tribune at the peak of his success, Drake said that his mother bought him a tenor banjo while he was in high school in 1936, but was forced to sell it a year later "along with a great many other family possessions to raise funds for the necessities of life." The inexplicable part of this piece of his chronology is that by 1936, Drake was already 24 years old, an age at which he should have long been out of high school and capable of buying and selling his own musical instruments.

He served a year-long hitch with the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program charged with make-work tasks such as forest maintenance, then spent the pre-War years hoboing around the country. He moved back to the Bay Area in 1941, settling, finally, in Oakland, in a modest house on West Grand which he would occupy for the rest of his life. He got married the following year, although little is known about his wife. A heart condition kept Drake out of the military; he spent the War years working in shipyards instead. At some point after the War he took a job as a truck driver, the occupation that would sustain him until the success of "Transfusion."

Zorch, Man It's Nervous

Zorch, Man It's NervousIn 1950, San Francisco radio station KCBS introduced a nightly half-hour comedy program hosted by former big band trombonist Red Blanchard, a five-year airwaves veteran. This was no deejay show, however -- although he would spin the occasional novelty platter (with Red Ingle & The Natural Seven being a personal favorite), the centerpiece of The Red Blanchard Show was its jokes and sketches, tightly scripted to allow Blanchard to focus on his characters and dialects. The show's target audience was schoolkids and teens, a group of whom would pile into the studio each night to comprise a live audience.

Blanchard's show became a huge hit in the Bay Area, peaking in the summer of 1953. Its popularity prompted him to cut a series of novelty records of his own. Backed by Paul Weston & His Orchestra, Blanchard's biggest hit was a 1955 Columbia release entitled "Captain Hideous," with the title character a kind of clueless Flash Gordon. Its B-side was "Zorch!," whose lyrics demonstrated one of the lynchpins of Blanchard's radio show. Zorch was a mock-jive lingo created by his writers, inspired in part by Slim Gaillard, whose patois Blanchard had absorbed when their bands shared bills in the 1940s:

Edgar means it's dimph

Dimph means it's in there ...

Zorch, man it's nervous

Nervous, that's the most ...

Zorch, oh it's threatened

Threatened means it's new ...

Zorch, ain't it nervous

Nervous, it's the most

When some cat looks dimph to you

By 1953,

the 41-year-old truck-driver was fishing around for a way to get off the roads,

and set his sights on a career as a songwriter. His first move was to buy a

reel-to-reel tape recorder and a cheap second-hand piano. Next, he signed up

for a correspondence course in musical notation. "There were 96 lessons," he

said in the Tribune interview. "I learned to read music in the first

ten and quit. I haven't looked at the other 86." He then bought his king-sized

uke, more properly known as a baritone ukulele.

By 1953,

the 41-year-old truck-driver was fishing around for a way to get off the roads,

and set his sights on a career as a songwriter. His first move was to buy a

reel-to-reel tape recorder and a cheap second-hand piano. Next, he signed up

for a correspondence course in musical notation. "There were 96 lessons," he

said in the Tribune interview. "I learned to read music in the first

ten and quit. I haven't looked at the other 86." He then bought his king-sized

uke, more properly known as a baritone ukulele.

Also in 1953 Drake wrote "The Bully Bully Man," based on one of Blanchard's characters. The song would eventually be recorded by The Paris Sisters (from San Francisco, and later of Phil Spector/"I Love How You Love Me" fame) and released on the Cavalier label as the flip side to another Blanchard-associated number, "Zorch Boogie" (not to be confused with the aforementioned "Zorch!"). The release date of this record remains unknown, and thus it can't yet be placed chronologically amid "Transfusion" and the other Dot releases. Until such information comes to light, this item must remain apart as an interesting asterisk to Drake's early career.

Drake purchased a half-page ad in a 1953 issue of the amateur tipsheet Songwriter's Review, announcing himself as a songwriter by including the entire lead sheet for "Little Cowboy." The ad had an unintended effect: instead of garnering responses from music industry professionals, it was answered by his fellow amateur songwriters, who offered to pay him to record demos of their material. He accepted, and began supplementing his truck driving income with these demo recordings. He set up a recording studio in his kitchen but, with the tape deck squeezed onto a countertop and hovering half-over the sink, it proved a bit intrusive and was moved into a spare bedroom instead. Capitalizing on some successful song placements, as well as on his low fee structure (one song for $7, two for $11), Drake's demo business grew in prominence within the lower rungs of the songwriting industry. By April 1956 he claimed, in another tipsheet ad, to have recorded some 3000 of the suckers. He was just getting started.

I Listen To Red In Bed

One of the many connections between Drake's career and Blanchard's is that each, in the summer of his respective peak popularity, was the subject of a feature article in both Time and Life magazines (consolidating their reporting and photography expenses since they were published by the same company). In Blanchard's 1953 Time article, the uncredited reporter wrote, "The jokes are frequently such morbid items as the jingle about a railroad train hitting a girl named Lucy; 'The track was juicy, the juice was Lucy'." Fans of "Transfusion" will recognize its blueprint in those few words. (The article goes on to say, "His fans are currently enrolling in an 'I Listen To Red In Bed' club," a joking reference to the show's 9:30 p.m. starting time. An unreleased Nervous Norvus song is titled after that same phrase.)

In 1955 Blanchard left KCBS for a morning show on KPOP in Los Angeles,

this one a regular record-spinning gig. It was some months before Drake was

able to learn of his idol's new whereabouts. Once he did, he sent Blanchard

a demo tape of a new song he'd written. In the wake of its success, Drake would

give varying accounts of the inspiration for "Transfusion." To the Oakland Tribune,

he said the idea was sparked by an article he'd read in the Oakland Tribune,

about a bad car accident. To Time, he gave an account that sounded more

like something out of a Chuck Berry song: "I was driving, see, cool like down

the freeway. A young kid in a twin pipe job come up on me fast on the right.

He was a goner. He cockeyed near cooled me, man. So I said, 'Jimmy, let's write

a song about this cool cat.' I don't even know the name of the guy. But I got

even. Man, I got even!"

In 1955 Blanchard left KCBS for a morning show on KPOP in Los Angeles,

this one a regular record-spinning gig. It was some months before Drake was

able to learn of his idol's new whereabouts. Once he did, he sent Blanchard

a demo tape of a new song he'd written. In the wake of its success, Drake would

give varying accounts of the inspiration for "Transfusion." To the Oakland Tribune,

he said the idea was sparked by an article he'd read in the Oakland Tribune,

about a bad car accident. To Time, he gave an account that sounded more

like something out of a Chuck Berry song: "I was driving, see, cool like down

the freeway. A young kid in a twin pipe job come up on me fast on the right.

He was a goner. He cockeyed near cooled me, man. So I said, 'Jimmy, let's write

a song about this cool cat.' I don't even know the name of the guy. But I got

even. Man, I got even!"

Jimmy Drake aspired strictly to songwriting success, and had no inclination to be a performer himself. Rather, he hoped that Blanchard would record his own version of "Transfusion." But Blanchard was so struck by the uniqueness of Drake's voice that he could hear no one but Drake doing it. "He had that very unusual voice," Blanchard said. "So, egad, there was nothing I could do with those demo records except put 'em on the air, instead of trying to sing 'em myself."

Ah, there was but one thing Blanchard thought to add to Drake's demo, one extra shot of hot sauce that became "Transfusion"'s defining touch. Working on a whim, he pulled a 78 from the Standard Sound Effects series out of KPOP's record library, cued it to "Auto Skids And Crashes," and played the brief track repeatedly to punctuate each mini-tale of wreckless driving that form the song's verses. "That was just a natural to add the crashes," says Blanchard. "It's almost like there was a pause there just right for it." He added the effect on the fly, manually cueing and recueing while Drake's demo played from another tape deck. "I did the whole thing in one afternoon."

Blanchard put the pastiched "Transfusion" on the air, where it was an immediate hit with his listeners. Before long, Randy Wood, president of Dot Records, called to see if the recording was still available for release. After making the deal, "I gave him the tape I had," says Blanchard, "and that's what they made the record out of, just that demo tape with the sound effects added."

|

| Wouldn't mind getting me one these ! |

The Norvus part Drake came up with on his own. "He just thought of a word to be alliterative with Nervous," says Blanchard. And so Nervous Norvus it was -- double-meaning, alliterative, and vastly cool.

Dot released "Transfusion" in May 1956, flipped with another brilliant novelty, the jaunty and equally hep "Dig" (Dot 15470). The record was unlike anything America had ever heard, and the country responded by making it an out-of-the-box sensation, reportedly snapping up a half-million copies within two weeks of its release, and going on to double that number before its run was through. Drake would earn the bulk of the artist royalties, of course, but Blanchard's share of one cent per copy was overshadowed by an unexpected third party -- the creators of the sound effects. "It turned out to be one of these commercial sound effect records. They recognized their crash and we had to pay them three cents a record." Blanchard, by the way, says he was paid royalties on sales of only 300,000 copies; most likely, his royalty statements were underreported while the press claims of a million copies were exaggerated.

Although it only hit #8 on Billboard, "Transfusion" remained on the chart for 14 weeks, and became a much bigger cultural phenomenon than the raw numbers can quite depict. At its height, "Transfusion" was popular enough and gory enough to be deemed a threat to the public order by both ABC and NBC radio networks, and it was banned from their airwaves. The song was big enough that it begat several cover versions, including a faithful knock-off by Scatman Crothers and a square harmony take by the 4 Jokers. (Both use the exact same crash effect as on the original, although it's unknown whether they got dunned for it, too.) And it was big enough that the producers of The Ed Sullivan Show invited Drake to lip-sync to it on the Sunday night variety staple. To most performers, an offer to appear on Sullivan's "really big shew" was a once-in-a-lifetime golden opportunity. But, according to Blanchard, "he chickened out. He was afraid to go -- he wouldn't appear in public." Although the hitmaking part of his career was certainly doomed anyway, with that decision Jimmy Drake virtually plunged the fork into it.

But the dénouement still remained. "Ape Call" was the follow-up, released in June, right on the heels of "Transfusion." Its storyline surrealistically mingles extinct species with contemporary jungle creatures, all looking for just one thing. The yells of a horny Tarzan, unleashed by Blanchard himself (keeping those extra royalty pennies in the family this time), made clear what that thing was. Once again, Drake was able to take his basic sound, combine it with threads gleaned from Blanchard's show (one line, for instance, begins, "When they dug a nervous chick ..."), and produce an ingenious two-and-a-half minutes of novelty music. Backed with the chilling hillbilly tale "The Wild Dogs Of Kentucky" (mislabeled in the singular), featuring the looped yelps of Drake as a mad hound, "Ape Call" peaked at #24 during its 10-week Billboard run (Dot 15485). In one of his ads, Drake boasted sales of a half-million copies.

|

| Looks like something Mr Bontempi would cover ! |

With the success of "Transfusion," Drake was able to quit his trucking job and turn to making music full-time. His demo orders continued to roll in, but they would have to wait, as he spent the latter half of 1956 traveling frequently between Oakland and Hollywood, where Dot had recently relocated from their own Tennessee origins. Soon enough, of course, he would return to grinding out cheap demos for amateur songwriters. Alas, if only they had been half as good as his Nervous Norvus recordings. Most, instead, are meager, joyless affairs, with no sound effects, no embellishments, and none of the verve, wit and imagination that sparked his best stuff.

In a 1959 ad promoting his demo service in Vellez Music News, Drake wrote that he "dramatizes novelty numbers with amazing little touches of pure showmanship." But most of those touches he reserved for Nervous Norvus, and thus the few post-Dot records he made under that name are of far greater interest to us than those he did as Singing Jimmy Drake. "Stoneage Woo," "I Like Girls," and "Does A Chinese Chicken Have A Pigtail" (the latter mislabeled minus the "Chicken," thus accentuating the ethnic slur), recorded for a couple of barely-existent San Francisco labels, are up to the standards of Drake's best work. Another excellent track, "Noon Balloon To Rangoon," was apparently intended as his fourth single for Dot, but was never released and is known today only by the fact that Dr. Demento has played an acetate of it on his own comedy radio show. Another of Drake's demos, "Kibble Kobble (The Flying Saucer Song)," commissioned by the Vellez label of Lomita, California (affiliated with the aforementioned magazine), is especially strong. It is highlighted by a ghostly vocal, Drake's best on any record.

Details of Drake's waning years are murky, and at present can be but speculated about. It is not known, for instance, for how long he continued his demo business, but a clue is that by the early '60s his once-frequent ads in the tipsheets had gradually wound to a halt. Rumors then began circulating that depicted a pathetic soul, who'd never had a girlfriend, let alone a wife; who'd never lived apart from his mother; who took his own life when he found his mother dead. The few shreds of documentation that exist contradict these stories, but corroborate with one more, that Drake drank himself to death. On July 24, 1968, Jimmy Drake died, age 56, in an Alameda County hospital, of cirrhosis of the liver. His body was donated to the University of California Anatomy Department.

In his interview in Time magazine back when things were still swell, Nervous Norvus, aka Jimmy Drake, had spoken of his songwriting method. The words seem equally suitable as his epitaph: "All I do is just take it easy. I sit in my own backyard, and I got dark glasses on. ... I take it cool, and there's nobody irritating me in my own backyard."

Thanks to Mr Milstein wherever you may be ?

Stay Zorch Daddy-O !!!

No comments:

Post a Comment